What is Texas German?

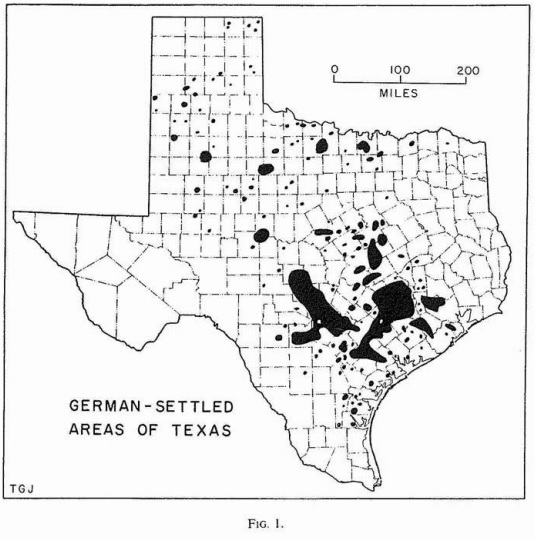

Texas German descended from a group of dialects spoken by the early German settlers in Texas. Immigration from Germany to the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico began in the 1840s. Texas German is not a single dialect, and it is spoken differently in different areas of Texas. It is a mixture of the dialects that the original German immigrants spoke, combined with English and some natural language change over time.

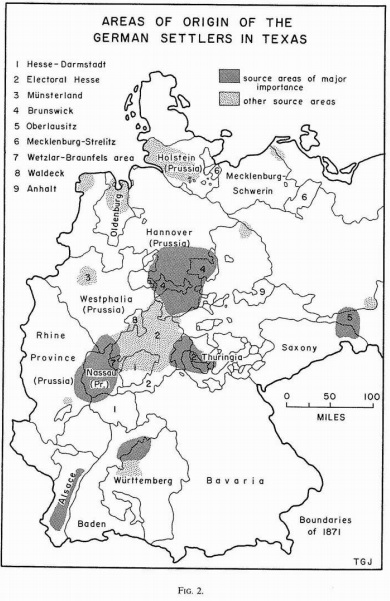

The images below are from Terry G. Jordan (1977) The German Element in Texas: An Overview.

Who speaks Texas German?

Texas German is spoken by people who grew up speaking German in Texas (or learned German at a very early age). Their ancestors came to Texas from Germany sometime between 1830 and 1900, and their families have remained in Texas ever since.

How unique is Texas German?

Texas is not the only place that Germans and German speakers settled in North America. Many Germans emigrated to Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, as well as many other states, as well as Canada and Mexico. Texas German is unique because there are no other German dialects like it in the U.S. or elsewhere in the world. Its differences lie in the distinct mix of different German dialects brought to Texas in the 19th century, its contact with Texas English, and its relatively young age.

The history of Texas German

The following is an excerpt from Hans C. Boas and Marc Pierce’s Lexical Developments in Texas German (2011) In: Putnam, Michael (ed.), Studies on German Language Islands. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. 129-150.

“The German language has a long history in Texas. Promises of land grants and transportation to Texas attracted a significant number of immigrants, mainly from northern and central Germany, beginning in the 1840s. By 1850 there were 8,266 German-born immigrants living in Texas (Jordan 1975: 48), and by 1860 there were approximately 30,000 Texas Germans, both immigrants and their American-born children (Jordan 1975: 54). German immigration to Texas eventually slackened, but the number of Texas Germans continued to increase: Eichhoff (1986) estimates that there were approximately 75,000–100,000 Texas Germans in 1907, Kloss (1977) states that in 1940 there were approximately 159,000 Texas Germans, and Nicolini (2004: 42) suggests that at the beginning of the twentieth century approximately 1/3 of all Texans were of German ancestry.

For the first several decades of German settlement in Texas, the Texas Germans were relatively isolated, thanks to a number of political and social factors, ranging from the anti-slavery views held by most German settlers to deliberate attempts at self-sufficiency (see Salmons 1983 and Benjamin 1909, respectively, on these points). This isolation, coupled with serious attempts at language maintenance, allowed for the development and spread of TxG: there were 145 church congregations offering German-language church services as of 1917 (Salmons & Lucht 2006: 168); there were numerous German-language newspapers and periodicals, some with very healthy circulation numbers (Texas Vorwärts, published in Austin, had a circulation of approximately 6100 in 1900, according to Salmons & Lucht 2006: 174); there was a wide range of German literature written in Texas; there were German-language schools and numerous social organizations, including choirs, shooting clubs, and so on (see Nicolini 2004: 46–49 for further discussion of such groups).

This situation eventually changed dramatically, starting with the passing of an English-only law for Texas public schools in 1909 (Salmons 1983: 188). World War I, especially following America’s entry into the war in 1917 and the resulting increase in anti-German sentiment, along with the passage of another English-only law for public schools in 1918 (Salmons 1983: 188), led to the stigmatization of German and the beginning of its decline. World War II reinforced the stigmas attached to Germany, Texas Germans, and the German language. Institutional support for the widespread maintenance and use of German was largely abandoned, with devastating consequences for TxG. German-language newspapers and periodicals stopped publishing (Das Wochenblatt, published in Austin, stopped publishing in 1940) or switched to English as the language of publication (the Neu-Braunfelser Zeitung was the last to switch to English, in December 1957); some German-language schools closed and German instruction was dropped in others; and German-speaking churches replaced German-language services with English-language ones.

After World War II, the increasing migration of non-German speakers to the traditional German enclaves and the general refusal of these newcomers to learn German led to the large-scale abandonment of German in the public sphere. The increased use of English in the public domain pushed German even further into the private domain. At the same time, younger Texas Germans left the traditional German-speaking areas for employment, education, or military service (Jordan 1977; Wilson 1977), and consequently switched to English as their primary language, which in turn weakened their command of TxG. Also, Texas Germans increasingly married partners who could not speak German, and in such linguistically mixed marriages, English typically became the language of the household. Children raised in such households are typically monolingual in English, or have only a very limited command of TxG, normally a few stock phrases like prayers or profanities (Nicolini 2004; Boas 2005).

Finally, the development of the American interstate highway system starting in 1956 made the once-isolated TxG communities much more accessible. This new accessibility cut both ways, as it was now easier both for non-German speakers to visit or live in the originally German-speaking communities, and for German-speakers to accept employment in more urban areas. Both of these possibilities led to the spread of English at the expense of German.

Despite these factors, in the 1960s approximately 70,000 speakers of TxG remained in the “German belt,” which encompasses the area between Gillespie and Medina Counties in the west, Bell and Williamson Counties in the north, Burleson, Washington, Austin, and Fort Bend Counties in the east, and DeWitt, Karnes, and Wilson Counties in the south. Today, however, only an estimated 8–10,000 Texas Germans, primarily in their sixties or older, still speak TxG fluently (Boas 2003, 2005, 2009), and English has become the primary language for most Texas Germans in both private and public domains. With no signs of this language shift being halted or reversed and fluent speakers almost exclusively above the age of 60, TxG is now critically endangered and is expected to become extinct within the next 30 years.”

Works Cited:

Benjamin, Gilbert G. 1910[1974]. The Germans in Texas. New York NY: Appleton & Co.

Boas, Hans C. 2009. The Life and Death of Texas German. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Boas, Hans C. 2005. A dialect in search of its place: The use of Texas German in the public domain. In Transcontinental Encounters: Central Europe Meets the American Heartland, Craig Stephen Cravens & David John Zersen (eds), 78–102. Austin, TX: Concordia University Press.

Boas, Hans C. 2003. Tracing dialect death: The Texas German dialect project. In Proceedings of the 28th Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Julie Larson & Mary Paster (eds), 387–398. Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Eichhoff, Jürgen 1986. Die deutsche Sprache in Amerika. In Amerika und die Deutschen, Frank Trommler (ed.), 235–252. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Jordan, Terry. 1977. The German element in Texas. Rice University Studies 63(3): 1–11.

Jordan, Terry. 1975. German Seed in Texas Soil. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Kloss, Heinz. 1977. Die deutsche Schriftsprache bei den Amischen. In Deutsch als Muttersprache in Kanada: Berichte zur Gegenwartslage, Leopold Auberger, Heinz Kloss, & H. Rupp (eds), 97–98. Wiesbaden: Steiner.

Nicolini, Marcus. 2004. Deutsch in Texas. Münster: LIT Verlag.

Salmons, Joe. 1983. Issues in Texas German language maintenance and shift. Monatshefte 75: 187–196.

Salmons, Joe, & Lucht, Felicia. 2006. Standard German in Texas. In Studies in Contact Linguistics. Essays in Honor of Glenn G. Gilbert. Linda Thornburg & Janet Fuller (eds), 165–186. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Wilson, Joseph. 1977. The German Language in Central Texas Today. Rice University Studies 63(3): 47–58.

Linguistic aspects of Texas German

One of the things that makes Texas German distinct is its lexicon. Since Texas German is a mixture of many different dialects, and Texas German speakers from different areas speak differently, the wordlist below may not apply to every Texas German speaker, but it gives a glimpse into the dialect.

Bungis, der/die (buŋɡɪs) noun < En pumpkin, StG der Kürbis > A large rounded orange-yellow fruit with a thick rind, the flesh of which can be used in sweet or savory dishes.

Eichkatze, die (ˈaɪçˌ kat͡sə) noun < En squirrel, StG das Eichhörchen > An agile tree-dwelling rodent with a bush tail, typically feeding on nuts and seeds.

hiedas (ˈhiˌdas) determiner < En this, StG dieses > Used to identify a specific person or thing close at hand or being indicated or experienced.

Luftschiff, das (ˈlʊ1ˌʃɪf) noun < En airplane, StG das Flugzeug > A powered flying vehicle with fixed wings and a weight greater than that of the air it displaces.

mitaus (mɪt aʊ̯s) preposition < En without, StG ohne > In the absence of.

Stinkkatze, die (ˈʃtɪŋkˌkat͡sə) noun < En skunk, StG das Stinktier > A cat-sized American mammal of the weasel family, with distinctive black-and-white striped fur.

wasever (vas ˈeː.vaː) relative pronoun & determiner < En whatever, StG was auch immer > Used to emphasize a lack of restriction in referring to any thing or amount, no matter what.

Wasserkrahn, der (ˈvasɐˌkʁaːn) noun < En water faucet, StG der Wasserhahn > A device by which a flow of water from a pipe or container can be controlled

En = English

StG = Standard German

More information about Texas German

There are many books and articles written about Texas Germans. For an introduction to Texas Germans, the following works are a good place to start.

Boas, Hans C. 2009. The life and death of Texas German. Durham: Duke University Press.

Biesele, Rudolph. 1928. The history of the German settlements in Texas, 1831-1861.

Austin, TX: Press of Von Boeckmann-Jones Co.

Jordan, Gilbert J. 1977. The Texas German Language of the Western Hill Country. Rice University Studies, 63(3), 59-71.

Jordan, Terry. 1977. The German element in Texas. Rice University Studies 63(3): 1–11.

Jordan, Terry. 1975. German Seed in Texas Soil. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Wilson, Joseph. (1977). The German Language in Central Texas Today. Rice University Studies, 63(3), 47-58.

Gilbert, Glenn G. (1972). Linguistic Atlas of Texas German. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Gilbert, Glenn G. (1977). Origin and Present Day Location of German Speakers in Texas: A Statistical Interpretation. Rice University Studies, 63(3), 21-34.